How to Beat the Odds: Avoid Packaging Pinholes

Packaging engineers are familiar with this common packaging failure: the dreaded pinhole. Having been through it myself as a medical device packaging engineer—and helping customers design and analyze their packaging as the Technical Director at Oliver Healthcare Packaging—I’ve learned how to reduce or avoid pinholes altogether. When packaging failures are discovered in the eleventh hour of a product launch, there can be a significant impact to the overall cost and speed of the project.

When I work with customers, it’s important to look at each issue like a detective might view a crime investigation, knowing that things are not always as they appear to be. In a crime, DNA testing can confirm or exonerate a suspect. In packaging, microscopic examination and testing can do the same.

There are three common causes of pinholes: flex cracking, abrasion, and straight-line puncture. Each result from exposure to a particular type of stress. Understanding breach types will help you to avoid them in your next packaging design.

FLEX CRACKING

Flex cracking causes pinholes from the repeated movement of the package during transit. Contributing factors include package material selection, head space in the primary package and carton, and device characteristics (weight, size). Creases and compound folds in the sterile barrier system can also increase the risk of flex cracking.

The consideration given to all of these factors can significantly affect the risk of flex cracking.

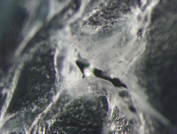

This microscopic magnification shows severe flex cracking marks and the resulting pinholes, confirming flex crack caused the failure.

ABRASION

Breach by abrasion can also initially present as a pinhole. Using our crime-scene investigation approach, confirming whether abrasion is the root cause can be determined with microscopic analysis of the pinhole and surrounding area.

Abrasion failures can originate from something inside the package (e.g. the medical device) or outside the package (e.g. the side wall of the carton) and are typically associated with repeated and focused contact and motion during transit.

Even a seemingly benign feature of a medical device (e.g. non-sharp hard edge or rounded tip) can cause an abrasion failure.

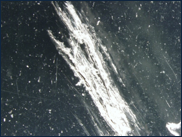

This microscopic magnification shows distinct abrading marks. The location and orientation of the pinholes from inside the pouch evidence an "exit wound."

Abrasion marks look distinctly different than flex cracking under a microscope. They can present as “scuff” or “scrape” marks in a linear orientation.

Making compound folds in packages to fit them into a carton that is too small can present risk as well. In this scenario, the resulting “point” of the fold can abrade against the sidewall of a carton until there is a breach.

While it may seem like a cost advantage to use a smaller shipper box, the savings must be weighed against the level of increased risk that comes with it.

STRAIGHT-LINE PUNCTURE

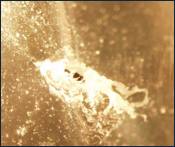

Under the microscope, a straight-line puncture may show little or no evidence of abrading or flex cracking.The "stand-alone" appearance of the pinhole(s) supports that it is a straight- line puncture, plain and simple.

This microscopic magnification of a straight-line puncture shows the pinhole(s) clearly. There are no abrasion or flex marks. The magnified view indicates that the puncture occurred from the inside out.

Microscopic magnification may tell you that the puncture is characteristic of an "exit" wound, originating inside the package. A puncture coming from something outside the packaging and creating a pinhole can also occur but in my experience is less common.

When a straight line puncture occurs, there are three questions to ask:

1. Can you associate the pinhole with a sharp component of the device and if so, can that sharp be mitigated?

2. Is there too much headspace in the carton, creating freedom of movement?

3. Has the appropriate packaging material (e.g. proper puncture resistance) been chosen for the device.

Unlike the damage caused by repetitive long-term vibration and motion, a puncture requires a focused force to breach the film. This damage is more of a "one-shot" event created by a severe hazard.

Puncture failures can sometimes appear at a consistent location in the package. This can help isolate the offending element.

Many details go into failure mode analysis. Having your packaging designed by experts and tested early can reduce the risk of failing a late stage transit study. Knowledgeable material selection is also critical to success. And when in doubt, don't go it alone. Talk to an experienced, industry-dedicated expert, whether supplier technical support folks or test labs or both.